Our History

History of the Bampton Morris

The origins of Morris dancing are lost in the mists of time and much disputed among scholars.![Moriskentänzer, one of 16 (now 10) wood Morris Dancers by Erasmus Grasser, Munich Stadtmuseum, 1480. (By user:shakko (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons) Moriskentänzer, one of 16 (now 10) wood Morris Dancers by Erasmus Grasser, Munich Stadtmuseum, 1480.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Moreska_Grasser01.jpg/256px-Moreska_Grasser01.jpg) What seems to be generally accepted is that Morris dancing probably has its roots in dances that originated in North Africa (“Moorish” dancing) as they were filtered through the cultures and courts of Europe on their way to these shores. The earliest references to the “Morys” date from the late 15th century and are found in a court context. There are references to Morris dancers in Shakespeare and one of his actors, William Kempe, famously Morris danced from London to Norwich in 1600 and reported his feat in a book that gave us the well known illustration of early Morris dancing accompanied by the pipe and tabor (which remained the traditional musical accompaniment until relatively recently). Around this time Morris dancing had become a common part of village celebrations.

What seems to be generally accepted is that Morris dancing probably has its roots in dances that originated in North Africa (“Moorish” dancing) as they were filtered through the cultures and courts of Europe on their way to these shores. The earliest references to the “Morys” date from the late 15th century and are found in a court context. There are references to Morris dancers in Shakespeare and one of his actors, William Kempe, famously Morris danced from London to Norwich in 1600 and reported his feat in a book that gave us the well known illustration of early Morris dancing accompanied by the pipe and tabor (which remained the traditional musical accompaniment until relatively recently). Around this time Morris dancing had become a common part of village celebrations. It was banned by Cromwell, but returned after Charles II and became a feature of rural seasonal festivities, particularly the Whitsun Ale. By the late 19th century the changing social landscape of Britain had reduced the Morris to just a few villages and towns when, in 1899, Cecil Sharp happened to witness a performance of the Headington Quarry Morrismen. For Sharp this sparked a lifelong interest in documenting the dances and the music of the surviving Morris sides. In the early twentieth century Sharp’s documentation and the enthusiasm of social activist Mary Neal made Morris dancing a cornerstone of a revived British interest in folk dance and music that continues to this day.

It was banned by Cromwell, but returned after Charles II and became a feature of rural seasonal festivities, particularly the Whitsun Ale. By the late 19th century the changing social landscape of Britain had reduced the Morris to just a few villages and towns when, in 1899, Cecil Sharp happened to witness a performance of the Headington Quarry Morrismen. For Sharp this sparked a lifelong interest in documenting the dances and the music of the surviving Morris sides. In the early twentieth century Sharp’s documentation and the enthusiasm of social activist Mary Neal made Morris dancing a cornerstone of a revived British interest in folk dance and music that continues to this day.

Bampton Morris

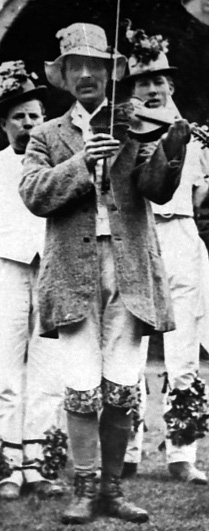

Local tradition claims that Morris dancing in Bampton goes back “at least 400 years” with some claiming a couple of additional centuries. The earliest documented reference to a Morris side in Bampton dates to 1847 when the Reverend J A Giles complained of a deterioration in the quality of the dancing, suggesting that a tradition of dancing was sufficiently well established to withstand a timely critique. The contemporary history of Bampton Morris begins with William (‘Jinky’ or ‘Jingy’) Wells (1868-1953) who came from a family of Bampton Morris dancers and joined the side in 1887 as the Fool. When Bampton’s long-time fiddle player Dick Butler abruptly left the side mid-performance in 1899 after breaking his fiddle in a drainpipe, Wells jumped in with his fiddle and the side carried on.(1) As the musician (and source of Sharp’s knowledge) of Bampton Morris, Wells shepherded the side through the First World War and on to a degree of fame in the early days of the English folk-dance revival.

And then there were two

In a town that cares passionately about Morris dancing there will inevitably be some upsets. In 1925, a leadership conflict arose within the team. Wells felt he should be the rightful leader through his long family connection with Bampton Morris. Most of the dancers of that day came from the Tanner family that had an equally long history with the side and they felt it should be one of them. As a result of this dispute (which also involved money, hard drinking, and perhaps even another broken fiddle)(2) Wells severed his connection with the side, ending a nearly 40-year relationship. In 1926, for the first time in memory, the Bampton side danced on Whitsun u

But the unity was not to last. In the early post war years two names became associated with Bampton Morris. Francis Shergold had begun dancing with Wells’ new side around 1935. Arnold Woodley followed his brother and two cousins into the traditional Tanner side, first dancing in 1938. As Wells became less able to lead the post-war side it was agreed that Shergold would be the Squire (leader) and Woodley would teach the dances. That arrangement lasted only a few years until 1950, when, during Whitsun practice, Woodley and Shergold disagreed about whether some dancers were up to performance standard.(3) Woodley felt so strongly about the quality of the dancing that he himself did not turn out for the Whit Monday dancing. Shortly after that Woodley, along with Thomas “Sonner” Townsend, another veteran of the Tanner side (first danced 1925), re-formed the traditional side and augmented it with younger dancers.

Although periods of illness throughout the 1960s forced Woodley to curtail his side’s activities, by 1970 the side was again out for the Whitsun dances and more as Woodley launched into an active period of touring outside Bampton, the highlight of which was a very successful tour of the east coast of the United States in August of 1982.

Arnold Woodley died in 1995, but the Bampton Morris tradition that he nurtured and preserved continues today in the Traditional Bampton Morris Dancers under the leadership of Woodley’s successor Lawrence Adams.

But now there are three

In his desire to preserve the Bampton Morris tradition, Arnold Woodley was known to be a demanding squire and a strict disciplinarian. For the younger dancers, nothing was more fear-inducing than to finish a dance and find Arnold’s fiddle bow pointing at you—that meant you hadn’t done it right and were in trouble. In February of 1974 the Traditional Bampton Morris Dancers along with the Bampton Traditional Morris Men (Shergold side) were invited by the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS) to a festival at the Albert Hall in London. They had performances on the Friday and Saturday, with a tea dance on the Sunday afternoon at Cecil Sharp House, home of the EDFSS. When the side pitched up for the Sunday dance there was disagreement as to whether the now somewhat crumpled outfits were necessary for this brief occasion. A consensus emerged for minimal attire, which was not the wish of the Squire. In what might be best described as a triumph of pique over common sense all of the rebellious dancers subsequently received letters from Woodley dismissing them from the side. These young men went on to form the third Bampton Morris side, the Bampton Morris Men.(5)

These days the Bampton Morris sides are not often seen outside of the town, but should you be fortunate enough to find yourself in Bampton on a Spring Bank Holiday (the modern substitute for Whit Monday) you will be treated to one of the purest examples of a fine old English tradition as interpreted by three different teams drawing upon their unique histories and traditions, and all with a passion worthy of the Morris.

Note 3: The source for this is Keith Chandler, 'Francis Shergold: Veteran Morris dancer, singer, musician ...', Musical Traditions, Article MT013 (no date, online).

Note 5: Thanks to Andrew Bathe, a member of the Woodley side at the time, for his recollection of this event in his privately published volume Arnold Woodley's Bampton Morris Photo Collection 1970-74.

Note 1. The source for this is Keith Chandler, Morris Dancing in the South Midlands: Morris Dancing at Bampton until 1914 (Minster Lovell: Keith Chandler, 1983) pp 25-26. Chandler relates that fiddler "... Dick Butler was having a disagreement with the dancers, either over the money he should get as fiddler or over the fact that the dancers sometimes got so drunk they fell about and got into fights with one another. One Whit Monday morning they were coming up from Weald and Butler caught his fiddle neck in a drainpipe and broke it. He was so relieved that he went home, whereupon 'Jingy' ran home to fetch his fiddle and played for the rest of the day." In a later publication Chandler dates this event to 1899 (Keith Chandler, '150 years of fiddle players and Morris dancing at Bampton, Oxfordshire', Musical Traditions, 10, 1992).

In the earlier paper Chandler quotes Wells himself attributing his accession to the role of fiddler to a dance event in 1908 at Weald Manor where the side unsuccessfully attempted to dance to a brass band. (Where their fiddler was is not reported.) Wells stated, "So the boys suggested that I should try the fiddle. I knew all the tunes so well that, although I had no music, all went well. So I gave up being the 'fool' and became the 'fiddler'..."

Whether or not a broken fiddle was involved it is clear that between around 1899 and 1908 Wells moved from the role of fool to that of fiddler.

Note 2. That Wells left the side and did not turn out for the Whit Monday dancing in 1926 is not in dispute, however there are differing versions of the reasons for this. Chandler notes (in Keith Chandler, The Archival Morris Photographs - 4: 'The Old 'uns and the Young 'uns', Bampton, Oxfordshire, 1927, English Dance and Song, XLVII, 3 (Autumn/Winter, 1985), pp. 26-28) one version that is commonly recalled in the village and even among the Morris sides is that following a visit to the Clanfield Feast, where some of the men got drunk and fell to fighting, George 'Nipper' Dixey (third from the right in the banner photo above) broke Wells' fiddle. This was subsequently mended, but, reportedly, Wells refused to play for the side again and later started his own side. In the same paper Chandler offers an extensive quote from Wells about the split, which contains no mention of a broken fiddle, but does point to serious disagreements (that probably had been simmering for some time) about who would lead the side, how the money would be split, and the general decorum of many of the dancers at paid performances.

So, was there another broken fiddle in Bampton Morris' history? Are two different tales being conflated? We may never be certain, however our fool, Barry Care M.B.E., has custody of an important relic of the time, a broken and poorly mended fiddle.

On the last practice before Whit Monday 'the fiddle' is carried around the Talbot Inn in a solemn procession by the squire of the side while libations of real ale are sprinkled about he practice courtyard, allegedly for good weather and no damaged knees on the following day. (Just kidding, and testing to see if anyone actually reads these notes.)

Note 4: Keith Chandler, 150 Years of Fiddle Players and Morris Dancing at Bampton, Oxfordshire, Musical Traditions, No 10, Spring 1992 (Article MT051).